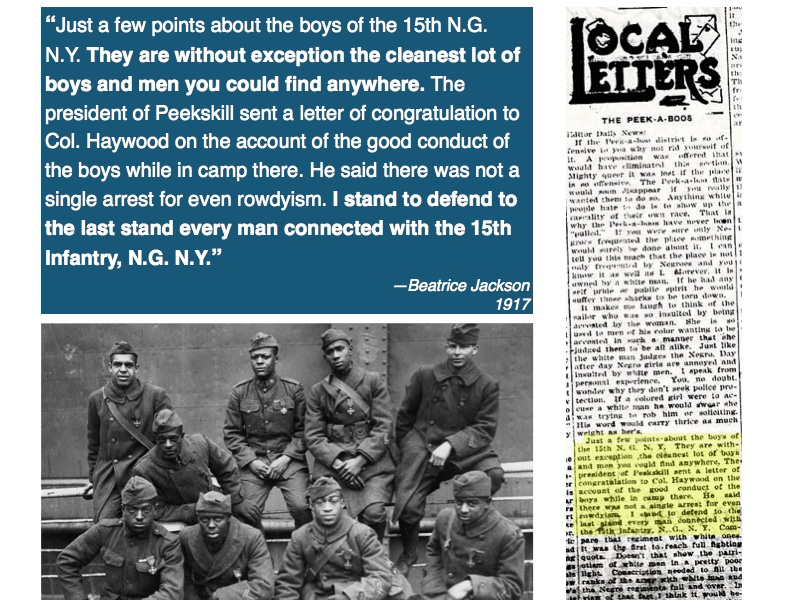

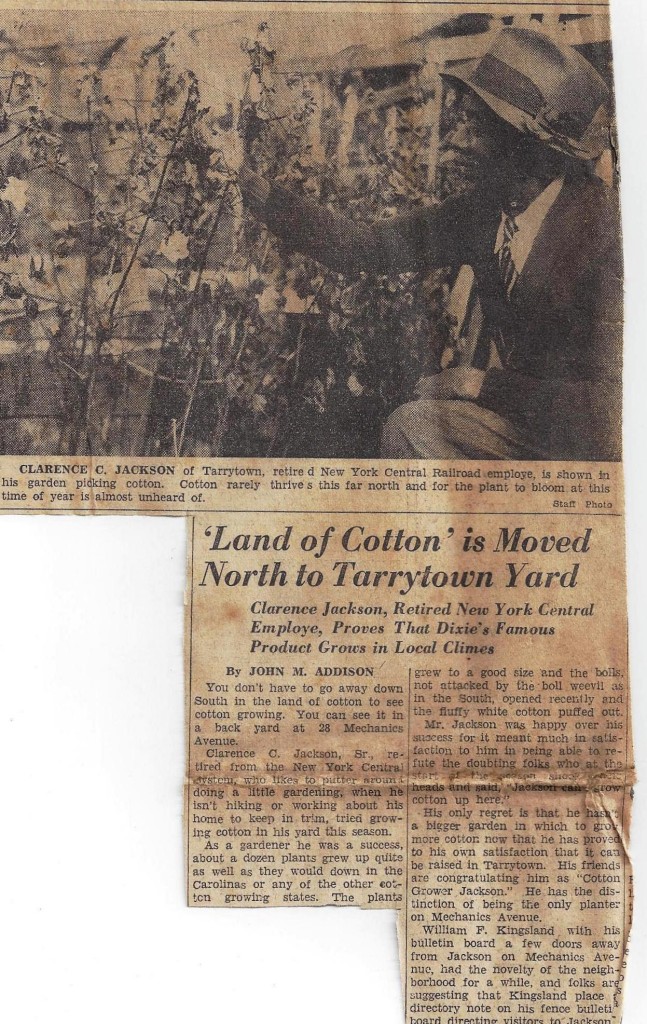

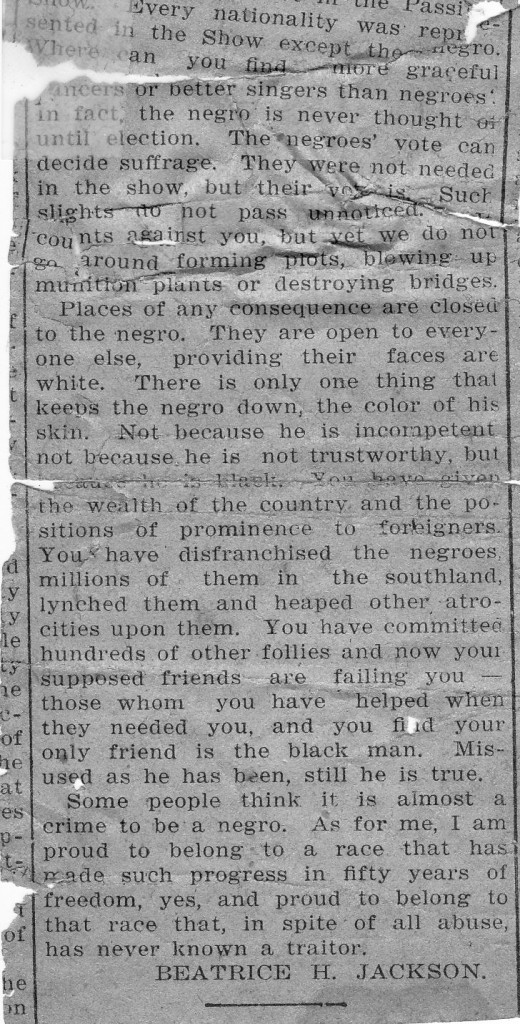

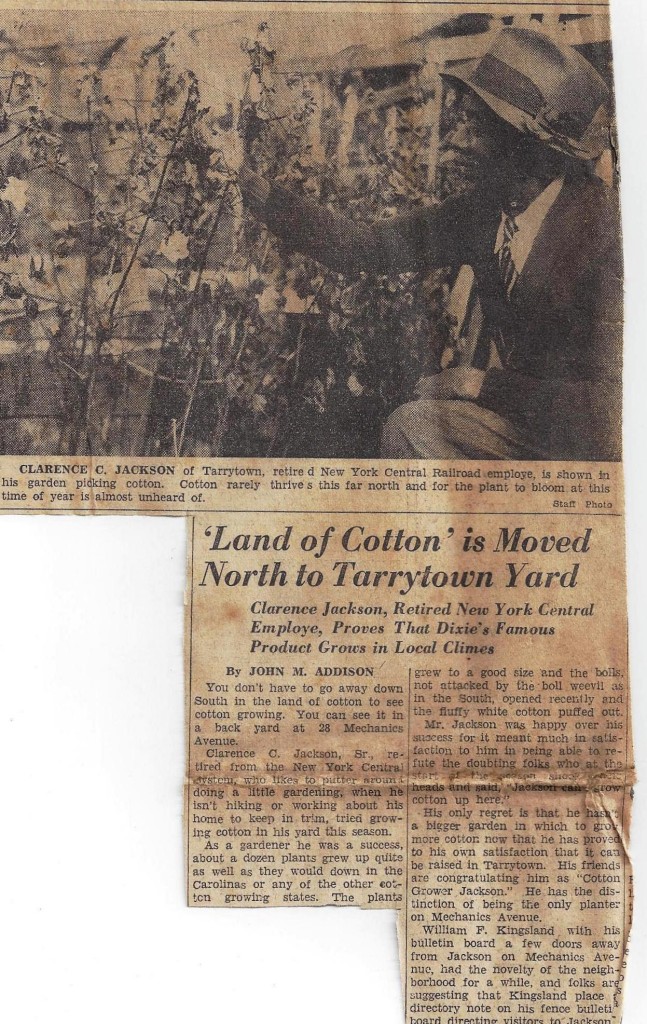

You don’t need to see the movie “12 Years a Slave” to know that Black folks have a history with cotton. Exposed to cotton as a child growing up in Virginia in the 1870s, my great grandfather, Clarence “Papa Jack” Jackson, earned newspaper headlines some 70 years later when he planted and grew cotton in New York state.

“Cotton rarely thrives this far north and for the plant to bloom at this time of year is almost unheard of,” a December 1941 newspaper account of “Papa Jack’s” cotton growing skills proclaimed.

“Cotton rarely thrives this far north and for the plant to bloom at this time of year is almost unheard of,” a December 1941 newspaper account of “Papa Jack’s” cotton growing skills proclaimed.

Told by family and friends that he couldn’t grow cotton in his backyard in Tarrytown, N. Y., “Papa Jack” set out to prove them wrong. “Mr. Jackson was happy over his success for it meant much satisfaction to him being able to refute the doubting folks who at the start of the season shook their heads and said, ‘Jackson can’t grow cotton up here,'” the 1941 article reported.

“Mr. Jackson only tried growing cotton as a fad, but as he kept cultivating it, the cotton kept growing and blossomed into as fine a plantation as one would find in the heart of the Carolinas or Tennessee,” an article published some years later said.

From this country’s beginnings, cotton was a focal point of the economy. Between 1800 and 1860, slave-produced cotton expanded from South Carolina and Georgia to newly colonized lands west of the Mississippi. This shift of the slave economy from the upper South (Virginia and Maryland) to the lower South was accompanied by a comparable shift of the enslaved African population to the lower South and West. By 1850, 1.8 million of the 2.5 million enslaved Africans employed in agriculture in the United States were working on cotton plantations, according to reports.

As has been said about the 2008 election of Barack Obama, “the hands that picked–and grew–cotton would someday pick a president.” Who knew?

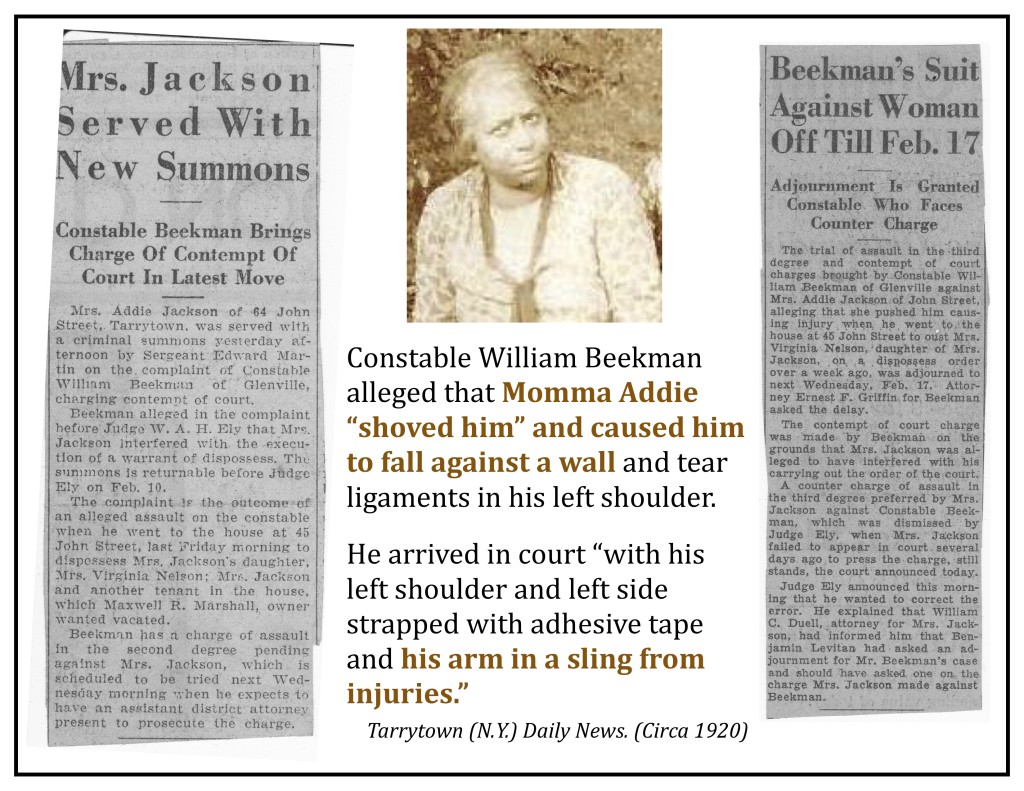

Constable William Beekman alleged that Momma Addie “shoved him” and caused him to fall against a wall and tear ligaments in his left shoulder, according to an article in an early 1920s issue of the Tarrytown Daily News.

Constable William Beekman alleged that Momma Addie “shoved him” and caused him to fall against a wall and tear ligaments in his left shoulder, according to an article in an early 1920s issue of the Tarrytown Daily News.