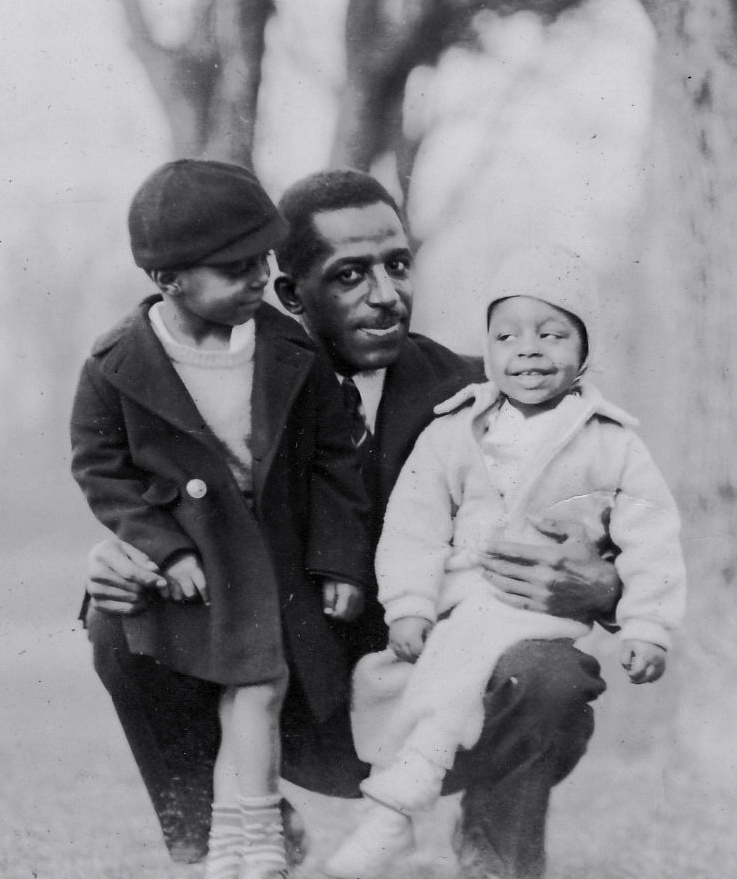

When my great uncle Clarence Channing Jackson Jr. took a position with the Baltimo re Department of Recreation in 1929 he made clear that his top priority was creating more recreational opportunities for the city’s black youth.

re Department of Recreation in 1929 he made clear that his top priority was creating more recreational opportunities for the city’s black youth.

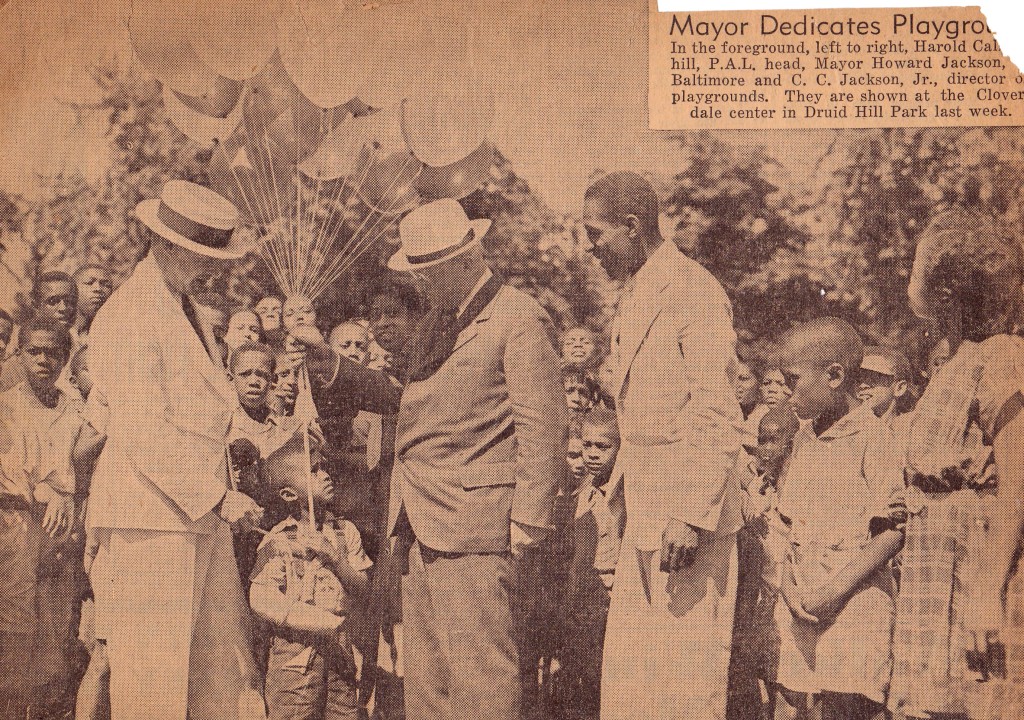

“I used every trick in the trade, every trick that I could command to gain facilities and opportunities” for black youth, Uncle Chan told a Baltimore newspaper. This included working with the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper to push for turning vacant lots into playing areas for black children.

Clarence Channing Jackson Jr. (Uncle Chan) joins the mayor of Baltimore at a playground dedication in the city’s Druid Hill Park section (circa 1935). “Mr. Jackson organized much of the first amateur sports activities for black Baltimoreans” an article said.

“As soon as he came to the city Mr. Jackson was given responsibility for the recreational activities of all the Negro children and their sports programs,” a 1963 Baltimore Sun article said.

Uncle Chan would go on to become the first black supervisor in the city’s Department of Recreation. Jackson “organized much of the first amateur sports activities for black Baltimoreans,” a newspaper article said following his death in 1972.

In 1977, the city honored Uncle Chan with the opening of the “C.C. Jackson Recreation Center” in north Baltimore. A proclamation issued at the building’s dedication said this about Uncle Chan: “He fought for expansion of opportunity for black children with tenacity blended with wisdom.”

In 1977, the city honored Uncle Chan with the opening of the “C.C. Jackson Recreation Center” in north Baltimore. A proclamation issued at the building’s dedication said this about Uncle Chan: “He fought for expansion of opportunity for black children with tenacity blended with wisdom.”

Ironically, though not surprisingly, a half-century earlier Uncle Chan’s mother, Addie Jackson, had argued for more recreational opportunities for black youth in Tarrytown, NY where Uncle Chan was born and raised.

Addressing an advisory group set up in the early 1900s to make recommendations for improving the village, Momma Addie said this: ‘There is no recreation for colored boys and girls in Tarrytown. The civic league does wonderful work, but outside of that there is no means of recreation provided for us.”

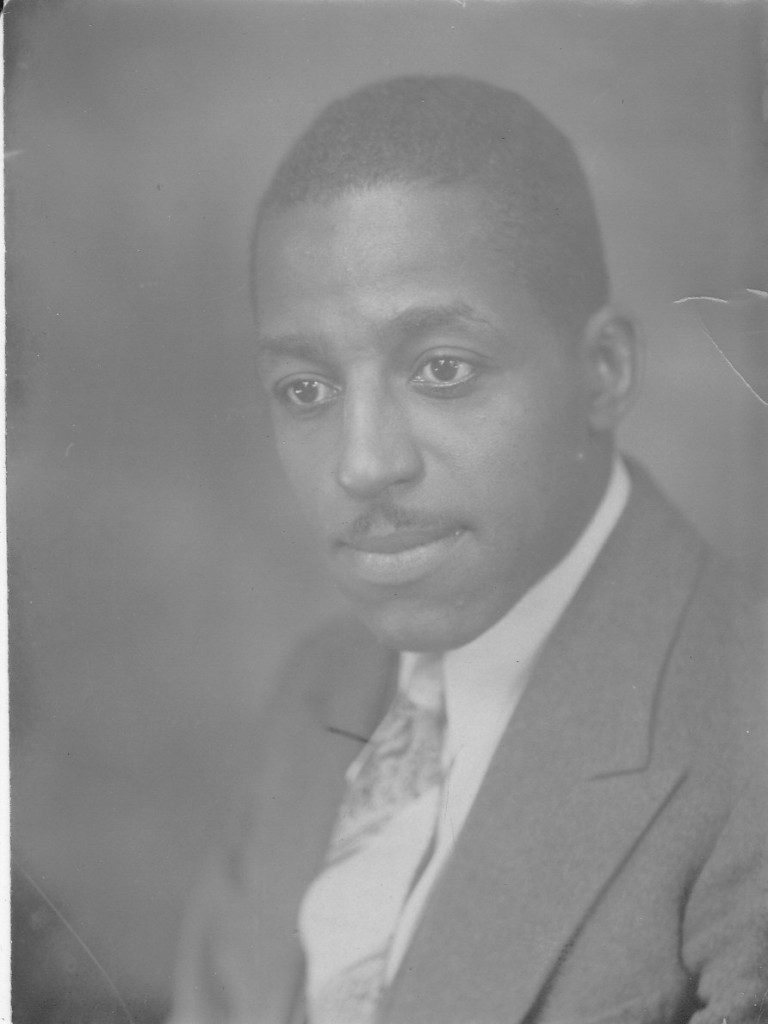

A Legendary High School Athlete

In the early 1920’s, Uncle Chan was a legendary high school athlete at Washington Irving High School in Tarrytown, NY., where he starred in football and track and field.

A 1961 newspaper article in the Tarrytown Daily News (N.Y.) recalled this headline from a Nov. 24, 1921 issue of the paper: “Chan Jackson Makes 65-Yard Run for Touchdown.”

“It was a common occurrence for young Jackson to make exceptional long runs and win games within seconds of the final period,” the article says.

His “terrific burst of speed and his ability to twist, turn, weave and dodge were executed quicker than the bat of an eyelid.”

Upon his graduation from Washington Irving in 1922, a newspaper editorial said this: “We are frank to admit that it will be some years before another Jackson is discovered. He is a wonder-athlete.”

Uncle Chan went on to star in track at Springfield College in Massachusetts and would later coach the first women’s track team to compete internationally.

While in college, Uncle Chan worked as a “red cap” at Grand Central Station in New York City during summer recess and the holidays. He would later call it a “tremendous experience” where he met famous people from around the world, learned about various people and their personalities, and watched gangsters being “taken up the river” to Sing Sing Prison.

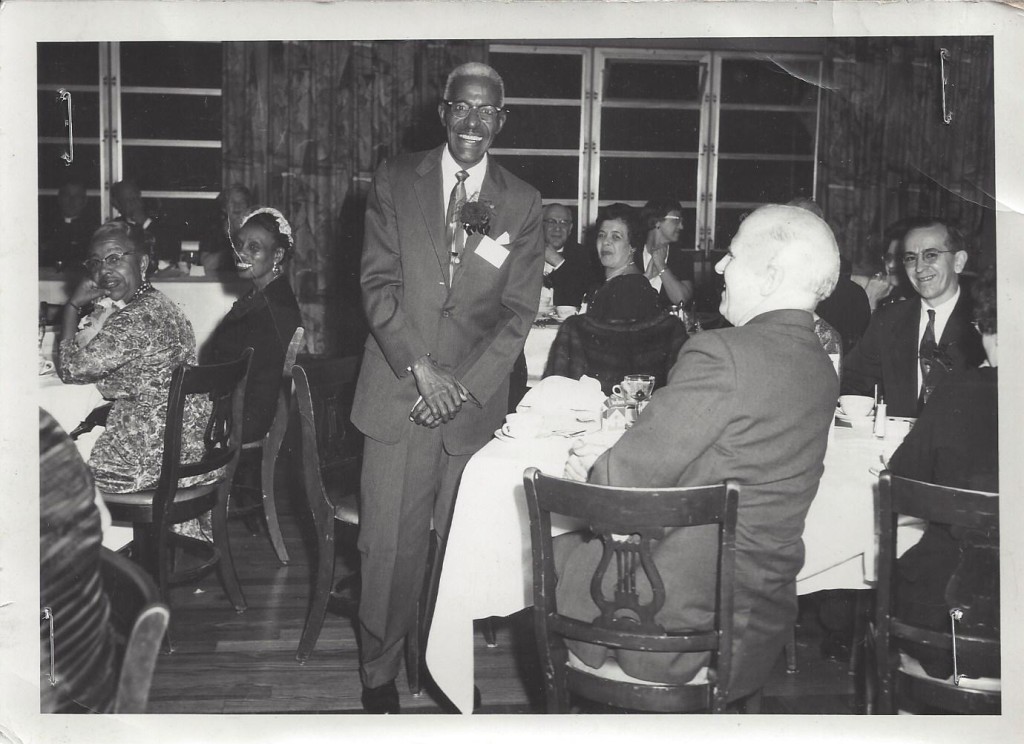

Clarence Channing Jackson Jr. is honored at a dinner in Tarrytown, NY where he was hailed as one of the greatest athletes ever at the town’s Washington Irving High School.

Clarence Channing Jackson Jr. saved his best and most important victories for the 1930s, 40s and ‘50s when he was a supervisor in Baltimore’s Department of Recreation. It was there that Uncle Chan used his talents and upbringing to fight segregation and create unprecedented opportunities for Baltimore’s black kids and families. And thus build on a tradition of racial solidarity and activism modeled by his mother and my great grandmother, Addie Jackson, and other members of our family.