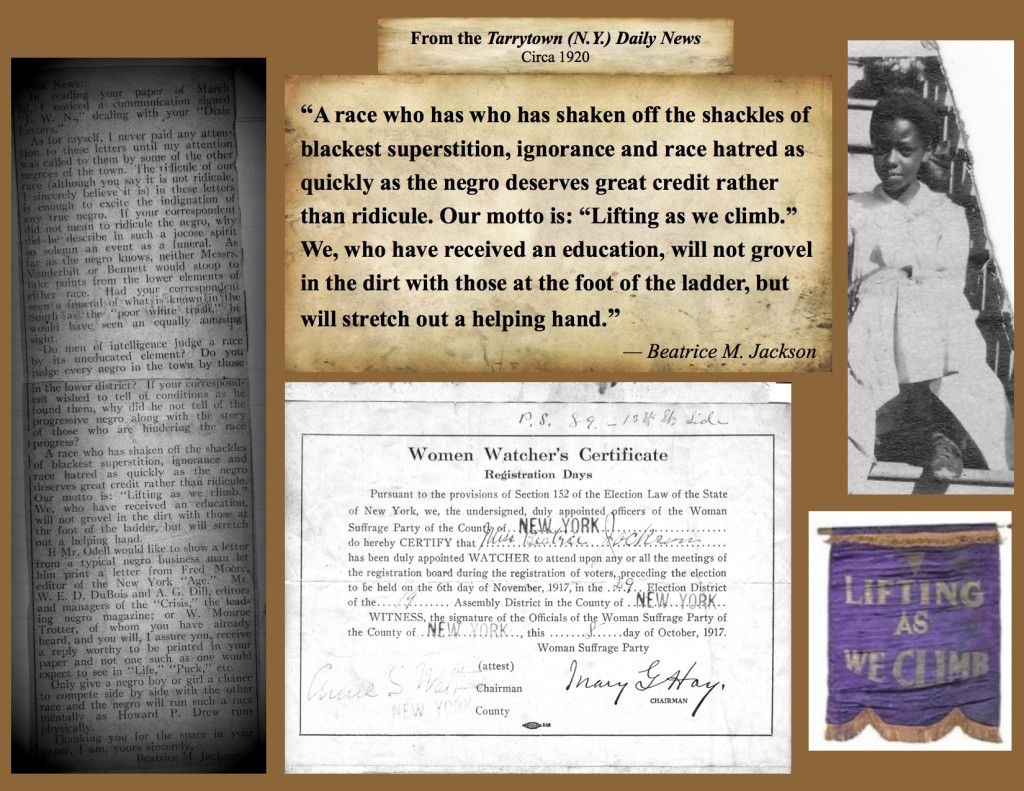

In August 2019, the Washington Informer newspaper published an article I wrote on the role that black women played in winning voting rights for women in New York state. My great grandmother, Addie Jackson, was one of the black women at the forefront of that effort. She’s singled out in a recent book on the women’s suffrage movement in NYS. Here’s the full Washington Informer article.

By Roger S. Glass

When voters in New York rejected a 1915 measure that would have given women in that state the right to vote an undaunted coalition of the state’s suffragist groups didn’t skip a beat. Led by the National American Woman Suffrage Association, they immediately began preparing for another referendum.

Two years later, in what is widely considered a watershed moment in the women’s suffrage movement, voters in New York state approved a referendum giving women there voting rights.

“Historians of the national suffrage movement suggest that the New York passage marked a pivotal point in the struggle for women’s votes because once New York enfranchised its female citizens, the emphasis of the movement shifted away from state-by-state campaigns to the federal campaign,” Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello wrote in their 2017 book, “Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State.”

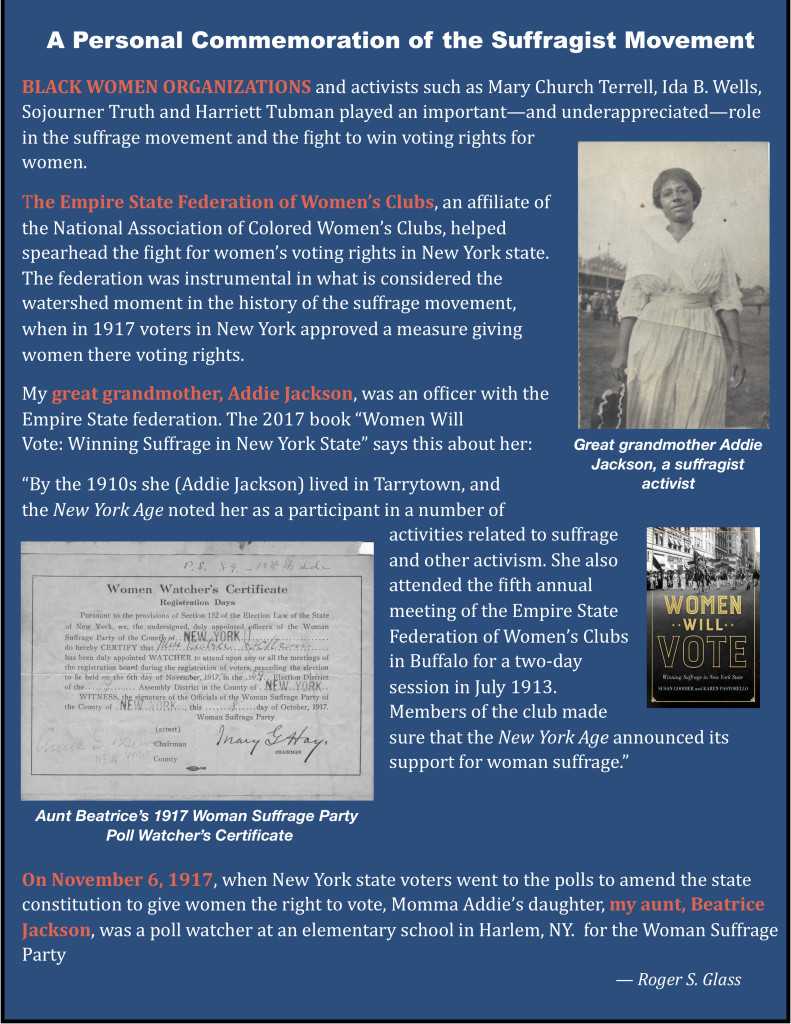

Great grandmother Addie Jackson

The coalition that came together to win voting rights for women in New York state included the Negro Women’s Business League and the Empire State Federation of Women’s Clubs, an affiliate of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC).

“Virtually every African American women’s club in the state advocated for suffrage regardless of the ostensible purpose of the organization. Black women, like white women, saw the vote as a panacea, able to solve their specific problems relating to racial violence, education, employment, and workers’ rights,” Goodier and Pastorello wrote in the introduction to their book.

My great-grandmother, Addie Jackson, was an active member of the Empire State Federation of Women’s Clubs, serving for several years as the organization’s financial secretary in the early 1900s. Goodier and Pastorello had this to say about my great grandmother in their book. “Any study of women of color confounds our understanding of class. The suffrage activist Addie Jackson, for example, took in washing and ironing, ‘day’s work,’ or housecleaning, in the Brooklyn area during the 1880s. Her class status improved significantly over the decades, as illustrated by her mobility and volunteerism.

“By the 1910s she lived in Tarrytown, and the New York Age noted her as a participant in a number of activities related to suffrage and other activism. She also attended the fifth annual meeting of the Empire State Federation of Women’s Clubs in Buffalo for a two-day session in July 1913. Members of the club made sure that the New York Age announced its support for woman suffrage.”

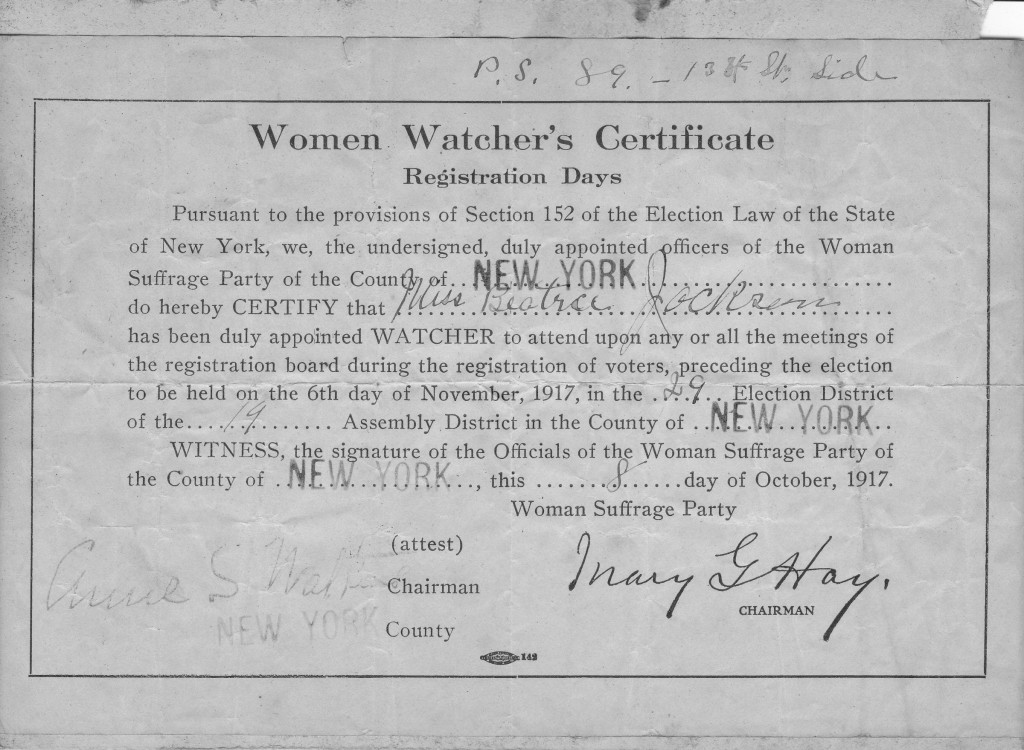

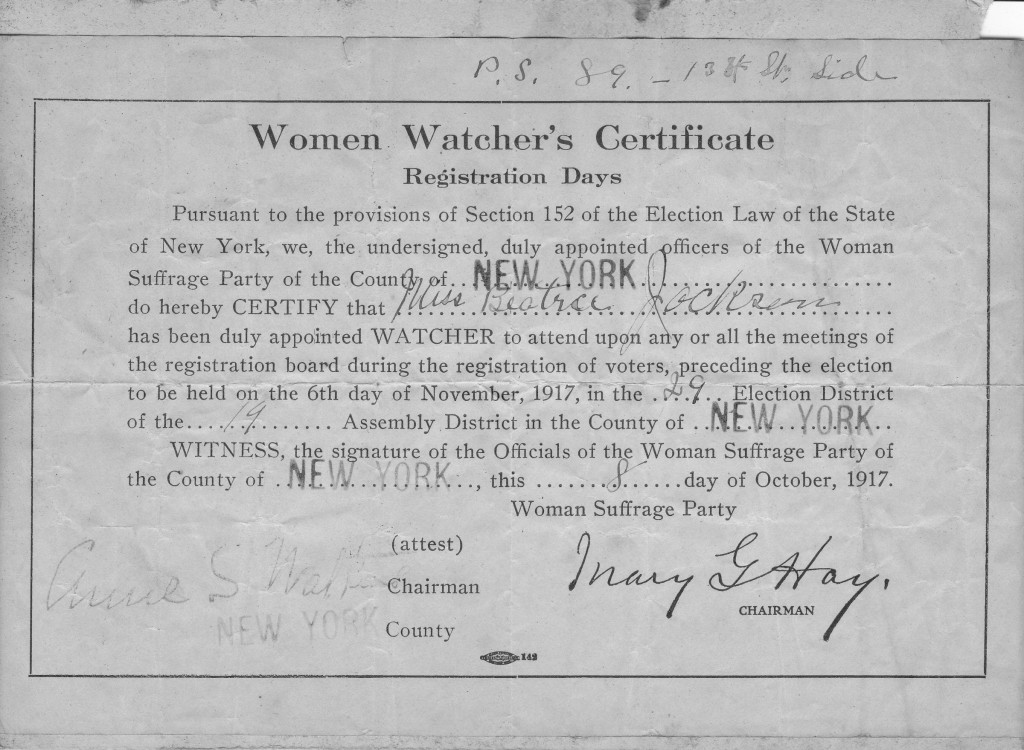

Aunt Beatrice Jackson’s 1917 Woman Suffrage Party registration card

In preparation for the 1917 vote, suffragists and their male supporters spread out across New York City and the state of New York to campaign for the referendum. One of the black women who registered to work on behalf of the Woman Suffrage Party was Addie Jackson’s daughter, my great aunt Beatrice Jackson.

Though just 22 years old at the time, Aunt Beatrice understood the significant role that black people could — and would — play in the suffrage movement. She wrote this in a Letter to the Editor published in the Tarrytown (N.Y.) Daily News. The letter was in response to blacks not being allowed to participate in a local Y.M.C.A. talent show.

“Every nationality was represented in the show except the negro. In fact the negro is never thought of until election. The negroes’ vote can decide suffrage. They were not needed for the show, but their vote is.”

On Nov. 6, 1917, Aunt Beatrice was a poll watcher for the suffrage party at an elementary school in Harlem, NY. On that day, a measure that would amend the New York state constitution and give women the right to vote won by 113, 000 votes.

“When New York women won the right to vote in 1917, they changed the national political landscape. The victory was a critical tipping point on the road to a constitutional amendment,”Huffington Post contributor Louise Bernikow, who has written extensively about the campaign to gain voting rights for women in New York state, told the blog New York Rediscovered.

A graduate of Howard University, Roger S. Glass is a former staffer for the Washington Afro-American newspaper. He recently retired after more than 30 years as a writer and editor for the American Federation of Teachers.