The past year has been extremely fruitful. I’ve had several opportunities to make presentations about my family history. Not so ironically, the first opportunity was on Juneteenth 2021 when I was invited to make a Zoom presentation at the monthly meeting of the DC chapter of the African American Historical & Genealogical Society (AAHGS). About 50 AAHGS members were on the call for my PowerPoint presentation.

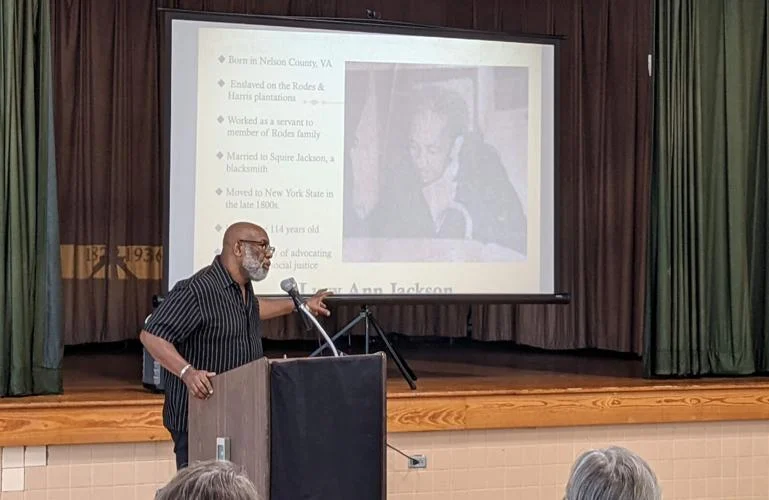

That was followed by a July 17 in-person presentation to the Nelson County (VA) Historical Society. Nelson County is where my great-great grandmother Lucy Ann Jackson was enslaved on the Rodes and Harris plantations until emancipation in 1865. I shared information about life for enslaved people in Nelson County in the early 1800s as well as published comments about plantation life made by Lucy Ann, who moved to New York state in the late 1800s and lived to be 113 years old.

Here’s the article:

By Nick Cropper

A hundred and fifty was a number that has been on Roger S. Glass’ mind as of late. It was roughly 150 years ago that his ancestors left Nelson County in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Glass on July 18 shared the story of his family’s legacy at the Nelson Heritage Center, including a former enslaved woman with ties to Nelson County, most of which he gleaned from a single family scrapbook dating back to about the early 20th century.

As Glass described it, the scrapbook which he happened upon in the basement of his parent’s home in Tarrytown, New York, roughly 11 years ago, is rich in newspaper clippings, photographs and other documents.

The findings paint a “pretty thorough” picture of his ancestors and their work toward social, racial and political activism.

“It’s a treasure to me,” Glass said, adding the discovery of the scrapbook would spark his interest in researching his lineage.

Dozens filled the auditorium of the Nelson Heritage Center — which served as the county’s former segregated high school until integration in the late 1960s — to hear of Lucy Ann Jackson, a former enslaved woman with ties to Nelson County who would go on to live to be older than 100 years old and claim the title of America’s oldest voter in 1936.

She registered to vote that same year and was believed to be as old as 114.

Jackson, having received an education from an early age, had a “spillover effect” on future generations to come and forged a legacy of advocating for Black communities that would be carried on her decedents, according to Glass, a former president of the Washington Association of Black Journalists and Jackson’s great-great-grandson.

For Glass, his great-great grandmother’s legacy demonstrates the importance of education, being socially and politically active and raising up others who were not afforded the same luxuries.

The Sunday-afternoon event marked a return to form for the Nelson County Historical Society as the nonprofit resumed its programs that had been put on hold because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Debbie Harvey, president of the historical society, said the event was a “long time coming” as officials initially had planned the program for June 2020.

According to the Nelson County Historical Society, Lucy Ann Jackson was enslaved in Nelson County until after the Civil War. She initially worked on the county’s Rhodes Plantation, which Harvey said she believed was located toward the Afton area, before later being sent to a plantation owned by Col. James Harris, whose family was one of the original settlers in the county.

“This is a very important, I think, distinction,” Glass said. “The noun slave implies that she was, at her core, a slave. The adjective enslaved reveals that, though in bondage, bondage is not her core existence. She was enslaved, but her essence was not a slave.”

Post Civil War, she and her husband, Squire, moved to Basic City — now Waynesboro — and eventually migrated to New York State in the late 1800s at the behest of her family.

During her time on the Rhodes Plantation, Lucy Ann Jackson received an education, in her own words, from the Rhodes family who taught her “from the cradle,” which she was quoted as saying in a 1936 article published in a Tarrytown newspaper.

“My great-great-grandmother was privileged, I believe,” Glass said. “I’m quite proud of the fact that I can look back and say that’s where we were fortunate enough to get started in our learning, if you will.”

Clarence Jackson, or “Papa Jack,” the firstborn of Lucy Ann and Squire Jackson and Glass’ great grandfather, moved to Tarrytown, New York, around 1885, Glass estimated, and was integral in forming a Baptist church there. He also was the personal assistant to different railroad magnets for 42 years.

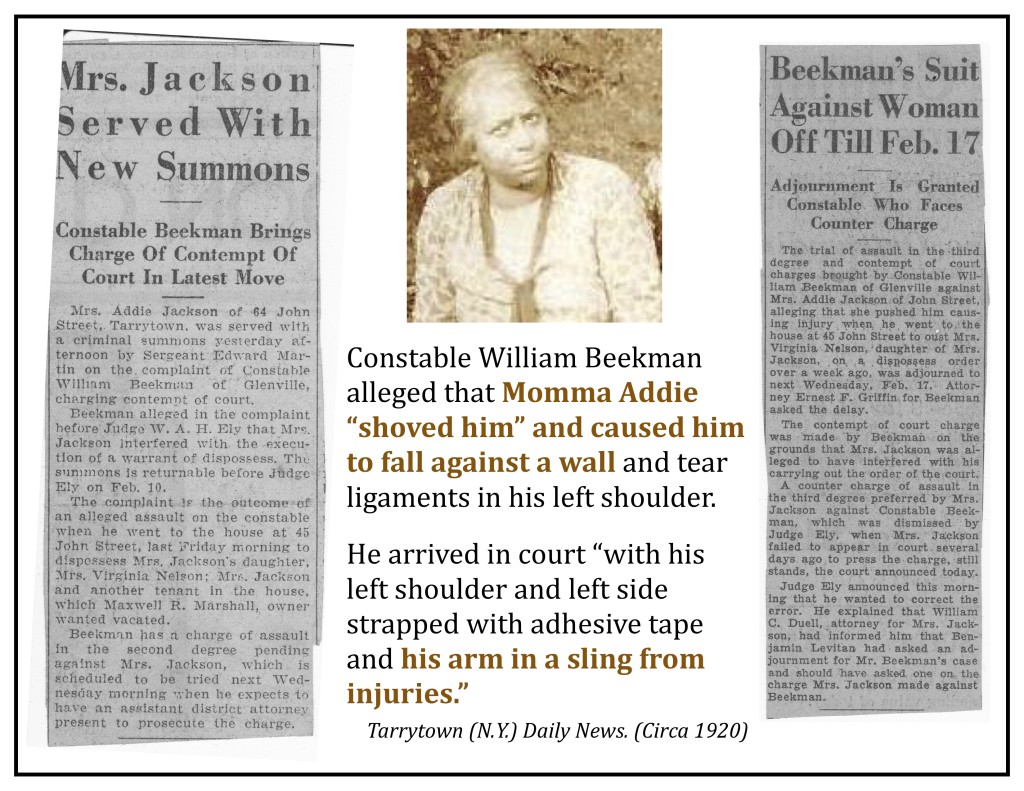

Addie Jackson, or “Mamma Addie,” was a strong-willed woman who dedicated to the welfare of her race and was “the colored spokesperson for the town of Tarrytown,” Glass said.

She advocated for recreational opportunities for the Black community. The city later formed a recreation center a few years later, to which she was elected president.

“They just didn’t talk about the needs of the colored community in Tarrytown, they acted on it and Mamma Addie was one of the leaders.”

“They just didn’t talk about the needs of the colored community in Tarrytown, they acted on it and Mamma Addie was one of the leaders,” Glass said.

Mamma Addie also formed a Red Cross chapter in her living room to ensure knitted goods were being given to Black soldiers during World War I. She served as a Republican party activist and president of the town’s Black Republican committee.

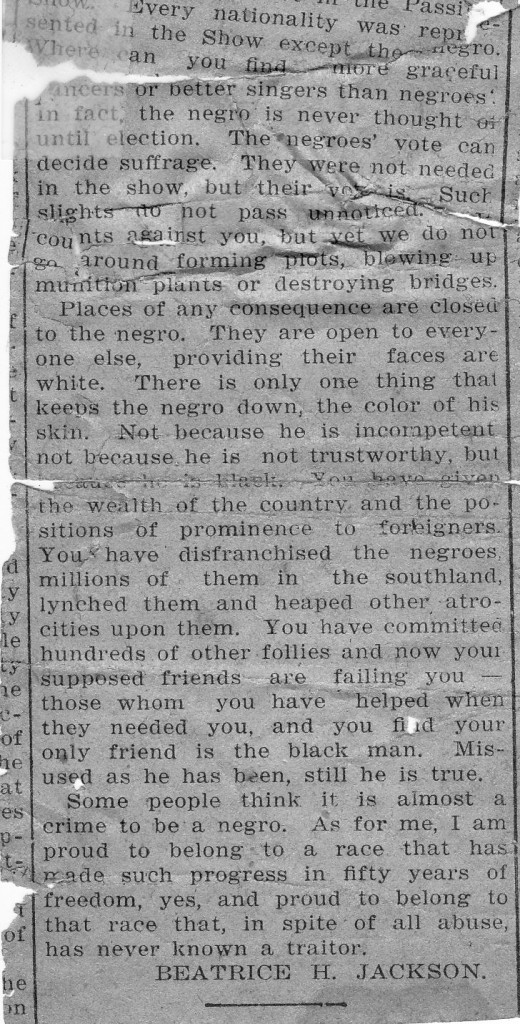

Glass also spoke of Beatrice Jackson, the first Black girl to graduate form Washington Irvin High School in Tarrytown. She was a performer and an avid defender of the Black community and often wrote editorials she would send to the local newspaper.

She died at the age of 28.

“It was regrettable because of all that she was capable of doing,” Glass said. “She was awesome. I can say that not because I was a part of her family, but because I know her.”

A history buff herself, Joy Loving, of Roseland, said the story of Beatrice Jackson and everything she had done for the Black community resonated with her in particular.

“I feel like so few of us know our history,” Loving said. “I wish I would hear more stories just like this that shows the impact one person had on every generation because Lucy Ann really like set the precedent for everyone in the Jackson family.”

Harvey said it was well worth the many months to hear the story of the Jackson family.

“I think the other advice is to go home and check your basements and your attics because you never know what riches you may find there,” Harvey said.

Before coming into his possession, Glass said he believed the scrapbook was repurposed by Mamma Addie. He noted the various photos and newspaper clippings concealed financial statements from the Empire State Colored Women’s Club and Mamma Addie was the club’s financial secretary.

Although the scrapbook paints a thorough picture, it is not complete. Glass said he is missing context for a lot of the photos found in the book and unfortunately a lot of family members who could have provided the much-needed context are now dead.

“I had to kind of stitch some things together but that scrapbook has been a remarkable source of information and inspiration for me,” Glass said.

While she would go on to claim the title of oldest living voter and is believed to have lived to be 114, Glass said there is potentially a roughly seven-year discrepancy in Lucy Ann Jackson’s actual age, depending on the source.

“I have different research that shows she was closer to 107,” Glass said. “That’s part of the struggle in researching family history, but for sure she lived to be over a hundred and for sure her legacy has endured.”