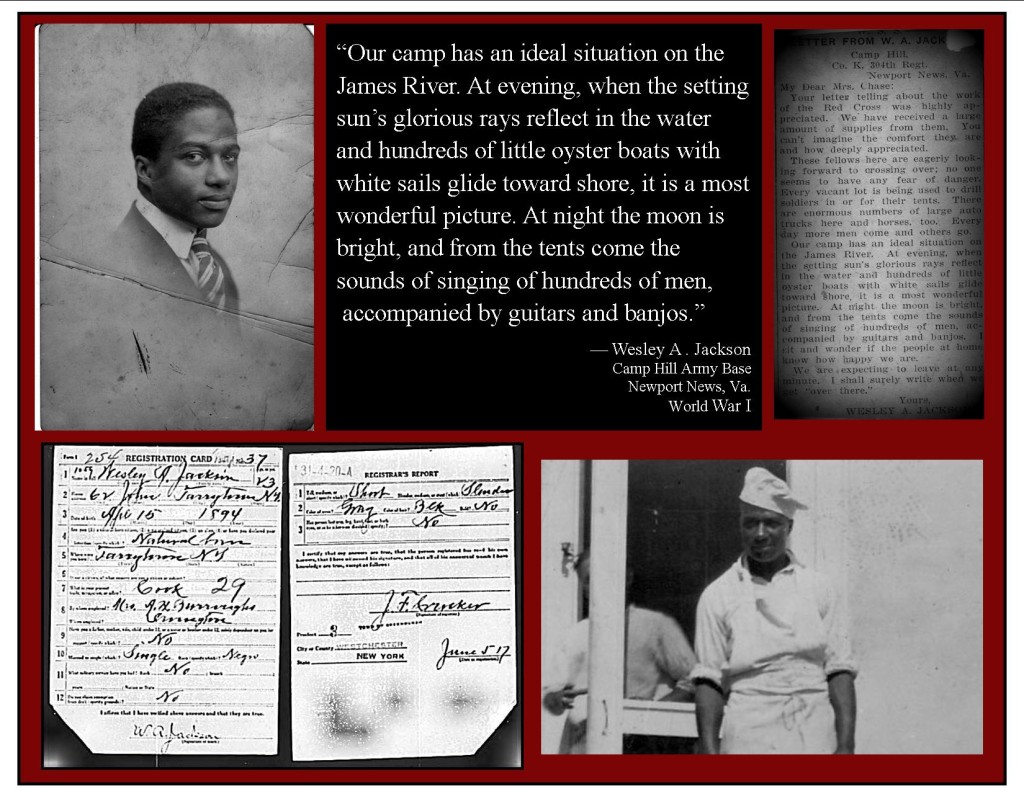

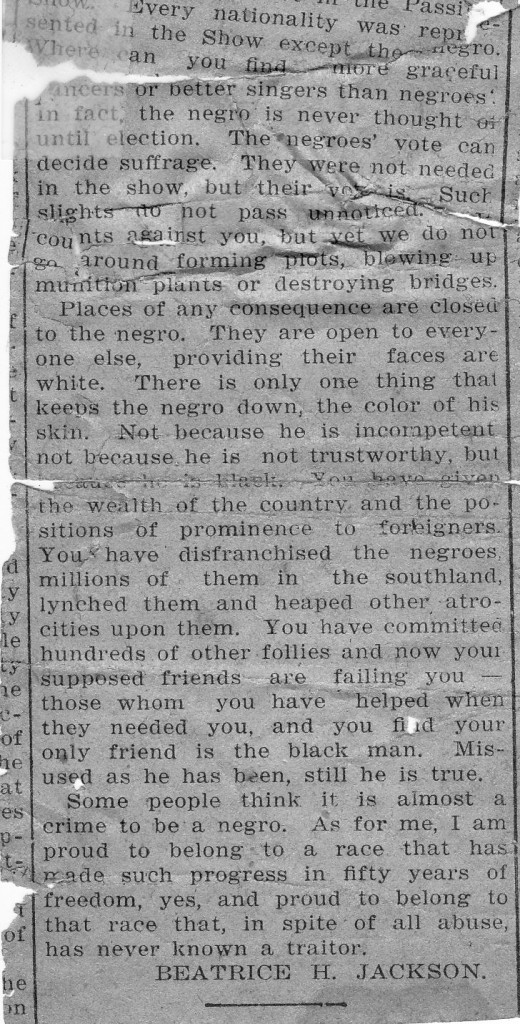

My great grandmother never missed an opportunity to support her race—often going the extra mile to do so.

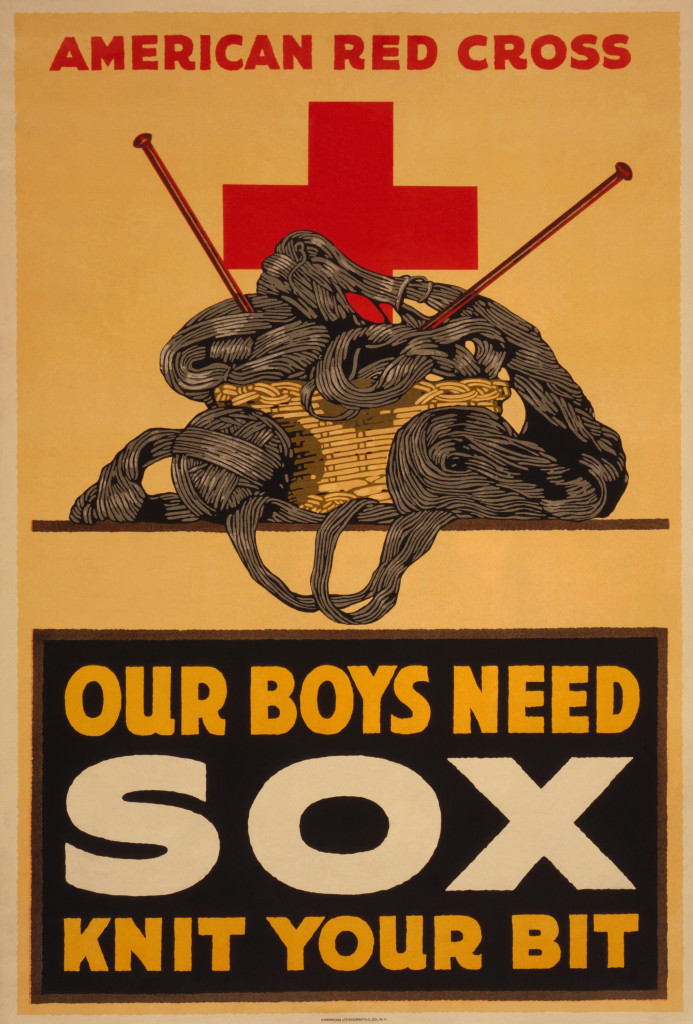

When Americans were encouraged to knit items for the troops during World War I my great grandmother, Addie Jackson, and her daughters—my grandmother Virginia and my aunt Marie—knitted socks, scarves and gloves for the servicemen.

“During World War I Americans of all ages were asked by the United States government to knit wool socks, sweaters, and other garments to warm American soldiers at home and abroad,” an article on HistoryLink.org says.

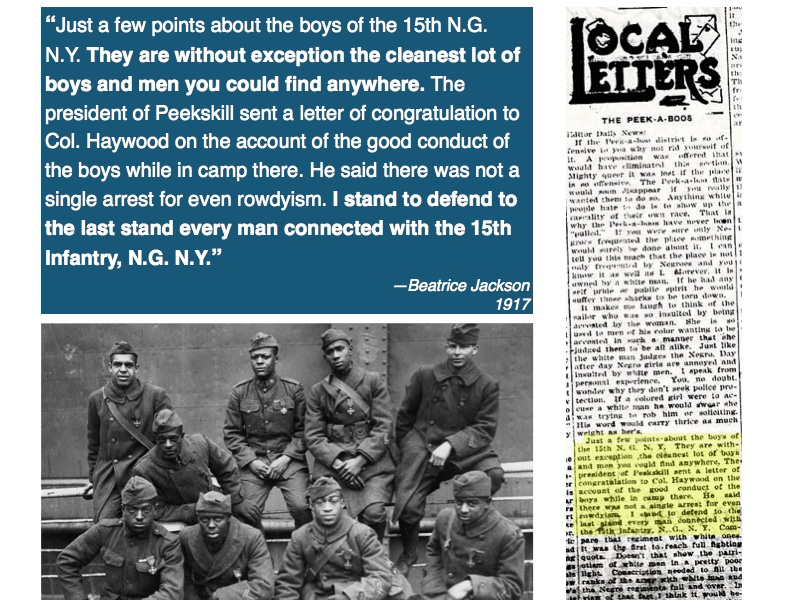

Members of the 369th Infantry Regiment from Harlem, NY during World War I. My family knitted socks, gloves and scarves for the regiment and other black soldiers.

“On Sundays in those days everyone would make a pair of socks and there’d be at least four pairs of socks by the end of the day and gloves and scarves by the end of the week,” my Aunt Marie said in a 1981 article published in the Tarrytown (N.Y.) Daily News.

However, when Momma Addie discovered the black soldiers were not being sent these clothing items, she started a Red Cross chapter in her Tarrytown, NY home, and began knitting and sending scarves, gloves and socks to the black troops.

Young black girls in Hampton, Virginia knit scarves, socks and other items for the World War I troops.

“We started the Red Cross in Tarrytown because it (the Red Cross) was segregated in those days,” my grandmother told the Tarrytown newspaper. “They wouldn’t take blacks and there were blacks fighting in the 369th Regiment. So mother started the Red Cross in our home.”

The 369th Infantry Regiment out of Harlem, NY had trained for battle in nearby Peekskill, NY, and my family knew some of its members. These were the black soldiers my great grandmother and her daughters had in mind when they started the Red Cross chapter in 1914.