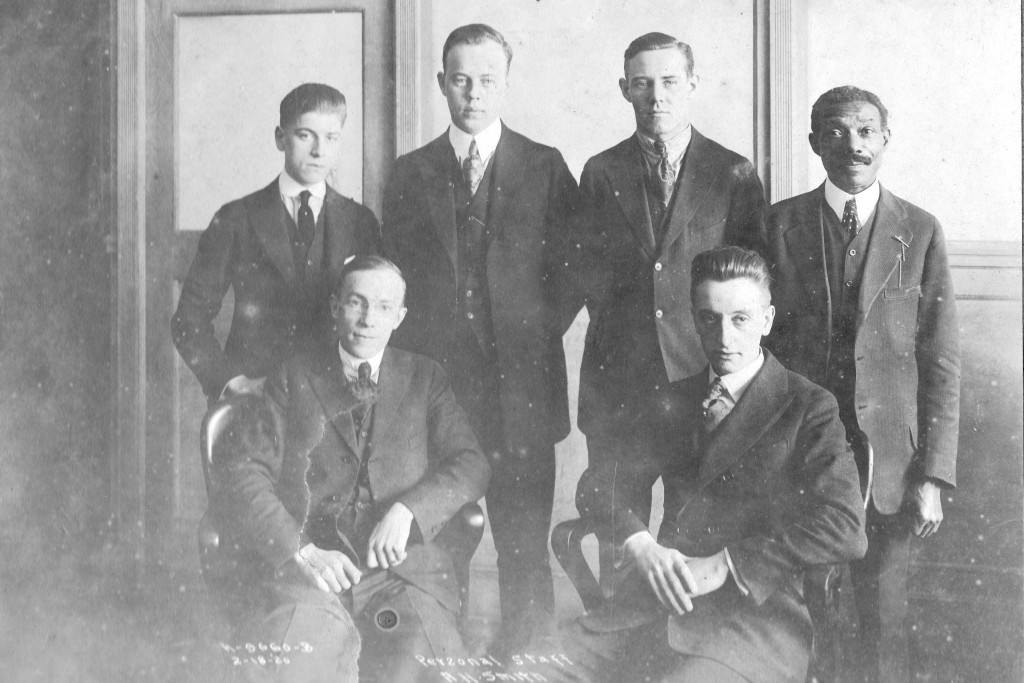

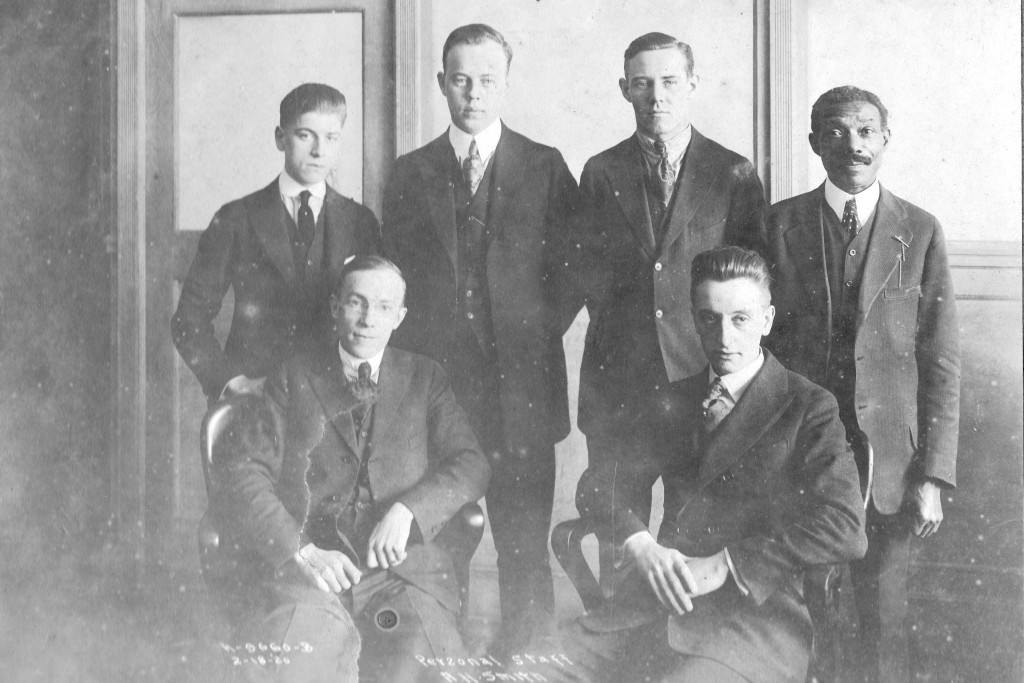

“Papa Jack” on the staff of railroad president A.H. Smith (seated on left) in 1920. My great grandfather is the good-looking 55 year old on the right.

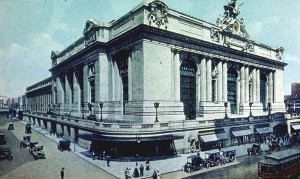

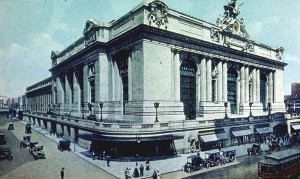

After migrating to New York state from his birthplace in southwestern Virgnia, my great grandfather, Clarence C. Jackson, settled in Tarrytown, a village served by the Hudson River Railroad. The railway line linked New York City and Albany and was one of the many railways that started and terminated at Grand Central Station in midtown Manhattan. The Hudson River line gave “Papa Jack” easy access to New York City–and job opportunities.

In 1892, at the age of 27, my great grandfather landed a job as a messenger with New York Central Railroad, whose offices were in Grand Central Station. He worked directly for the railroad’s president Chauncey Depew. In 1898, Depew stepped down as president of the railroad when he was elected U.S. Senator from New York. “Papa Jack” would work as a messenger for subsequent presidents of the railroad, eventually rising to the position of chauffer and personal assistant to A.H. Smith when he presided over New York Central Railroad (1914 -1924) during its heyday.

New York City’s Grand Central Station around 1915

I can imagine my great grandfather and his boss discussing their families, the war, race relations and an assortment of other topics during the ride from Smith’s estate in Westchester Co., N.Y, to his office at Grand Central Station. And it’s not a stretch to believe that the opinions and perspective of the wise and God-loving “Papa Jack” may have influenced some of the important decisions made by Smith, one of the most powerful men in America in the early 1900s.

I know that “Papa Jack’s” daughter, Virginia Jackson Nelson, had no problem giving people “advice.” Trust me on that, she was my grandmother.

My great grandfather retired on July 31, 1935 after working for eight of the railway system’s presidents. An article published in the Tarrytown Daily News the day before “Papa Jack” retired read: “Mr. Jackson met many dignitaries from all parts of the world” during his 42 years as an employee of New York Central Railroad.

I don’t know if they realized it at the time, but the “dignitaries” who met my great grandfather met a man who was a “dignitary” in his own right.

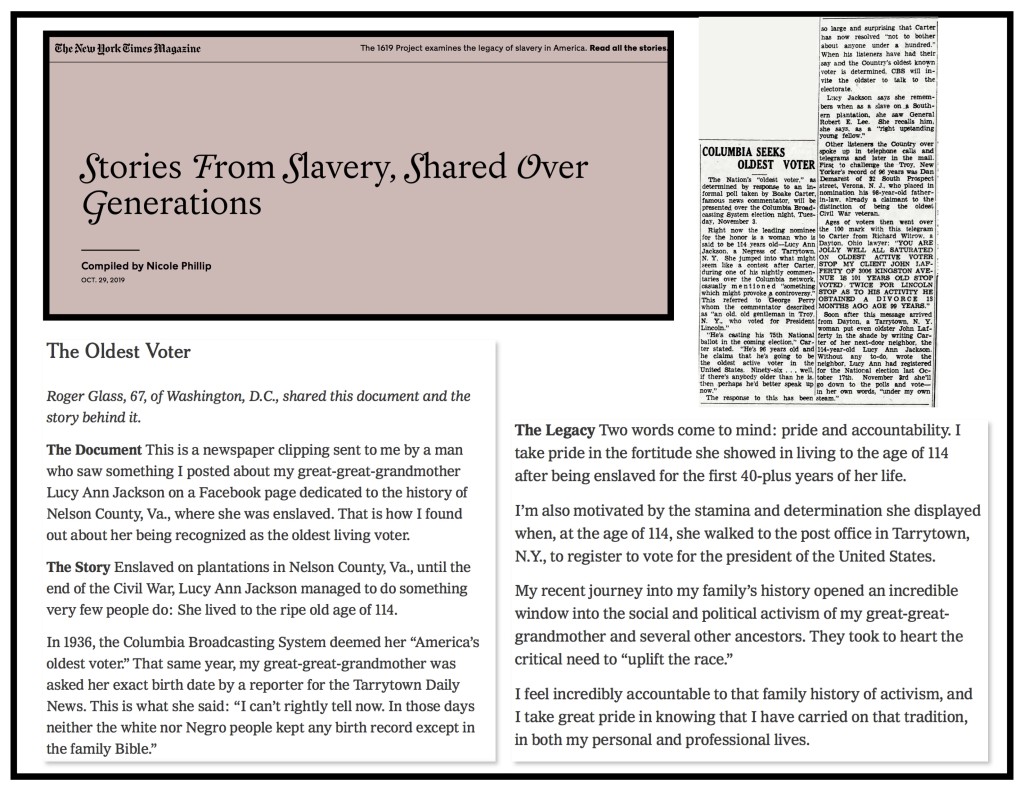

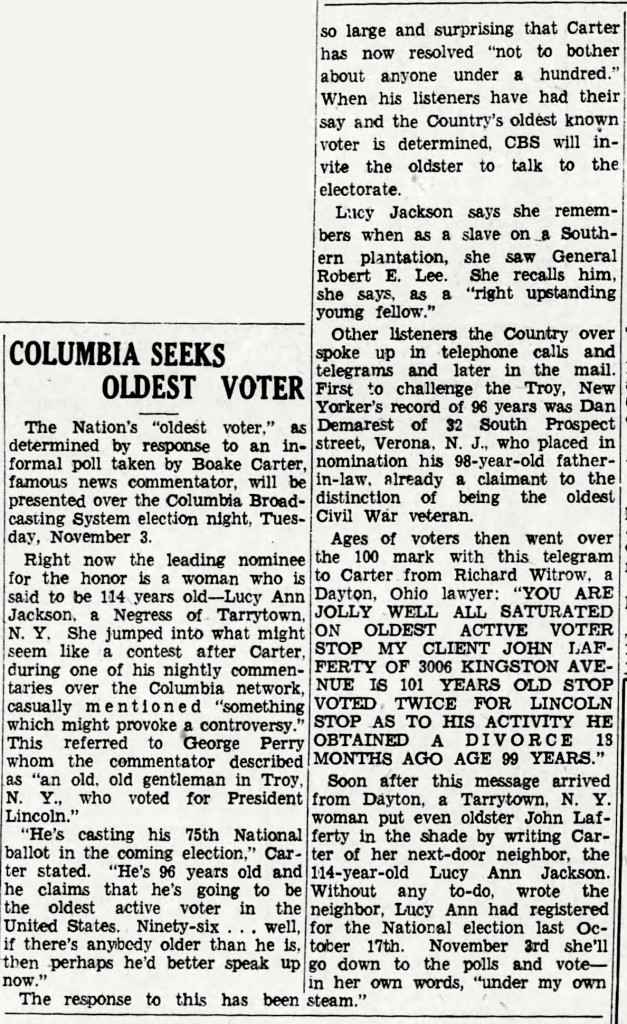

A piece of my family history was recently included in the New York Times’ 1619 Project. My entry (posted below) is a 1936 newspaper article about my great-great grandmother Lucy Ann Jackson. Enslaved on a plantation in southwest Virginia until shortly after the Civil War, my great-great grandmother was identified in that 1936 article as the nation’s “oldest voter” at the age of 114.

A piece of my family history was recently included in the New York Times’ 1619 Project. My entry (posted below) is a 1936 newspaper article about my great-great grandmother Lucy Ann Jackson. Enslaved on a plantation in southwest Virginia until shortly after the Civil War, my great-great grandmother was identified in that 1936 article as the nation’s “oldest voter” at the age of 114. American slavery is said to have begun in August of 1619 when a ship carrying 20 enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. The 1619 Project recognizes the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery and highlights the many contributions of the enslaved African–and those that followed in their footsteps.

American slavery is said to have begun in August of 1619 when a ship carrying 20 enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. The 1619 Project recognizes the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery and highlights the many contributions of the enslaved African–and those that followed in their footsteps.